Annika Lindberg

Denmark has become notorious for its repressive asylum and migration policy. Between 2015-20, more then 100 restrictive amendments or ‘stramninger’ were adopted with the declared aim to make life difficult for refugees and their families to lead a life in Denmark. Accordingly, their access to rights, freedom and protections were adapted to an absolute minimum standard: the time limit for temporary protection was reduced, and the right of family reunification for refugees suspended for three years (a decision later found by the European Court of Human Rights to violate human rights). A novel subsidiary protection status was also introduced (under chapter 7, article 3 of the Alien’s Act), which lowered the threshold for what constitutes such significant and sustainable improvements in the security situation in refugees’ countries of origin that they can ‘safely’ be deported. The protection status was primarily granted to people fleeing the war in Syria, in particular women and people of older age, who are not bound to undertake military service and therefore unlikely to obtain convention refugee status. This new, subsidiary protection status has turned out to have fatal consequences for thousands of people who are now threatened to have their protection status revoked and be deported to a war-torn country, where human rights organizations are reporting that returning refugees face disappearances, arbitrary imprisonment, and torture.

A ’paradigm shift’ from asylum to deportation policy

How did Denmark end up here? For decades, Danish asylum and immigration policy has been a laboratory for nationalist, populist, and racist politics, which has been adopted by conservative party blocks as well as social democratic governments. The repressive shifts in asylum law have been justified by racist discourses portraying people from so-called non-western countries – an administrative categorization used in Danish statistics, which often stands as a euphemism for Muslims – as threats to Denmark’s security, values, and welfare state. This trend culminated in 2019, when the incumbent conservative government declared a ‘paradigm shift’ in the country’s asylum policy: from now on, refugees were no longer supposed to be integrated but deported as soon as a slight improvement in the security situation could be discerned in the countries they had fled from. This deterrence policy tested the limits of how far refugees’ rights could legally be circumscribed. The Social Democratic government, which took office in 2019, have largely continued with a similar policy approach. In 2021, they announced their ambition to end asylum immigration altogether by externalizing asylum processing to an unknown country on the African continent.

The effects of the paradigm shift

The paradigm shift – which experts argue is rather a consolidation of several decades of restrictive migration policy – has had severe implications for refugees in Denmark. Refugees and their families have been placed in a permanent state of limbo, not knowing when their residence permits might be withdrawn. The unreasonably low ‘repatriation benefits’ have created poverty of the kind that human rights organizations argue are ‘unparalleled in the welfare state of Denmark’. Refugees who, in asylum processes that are not only exceptionally restrictive but often arbitrary, lose their residency risk deportation or to be sent to deportation camps (so-called departure centres). These prison-like camps are located in remote areas and are meant to put pressure on non-deported persons to leave Denmark by subjecting them to isolation, criminalization, and severely circumscribing their autonomy. Since residents are not de jure confined in the camps, they risk remaining there indefinitely. Migrant activists and researchers have highlighted how the camps are killing people slowly.

The Syrian refugees’ deportability and mobilization against deportation

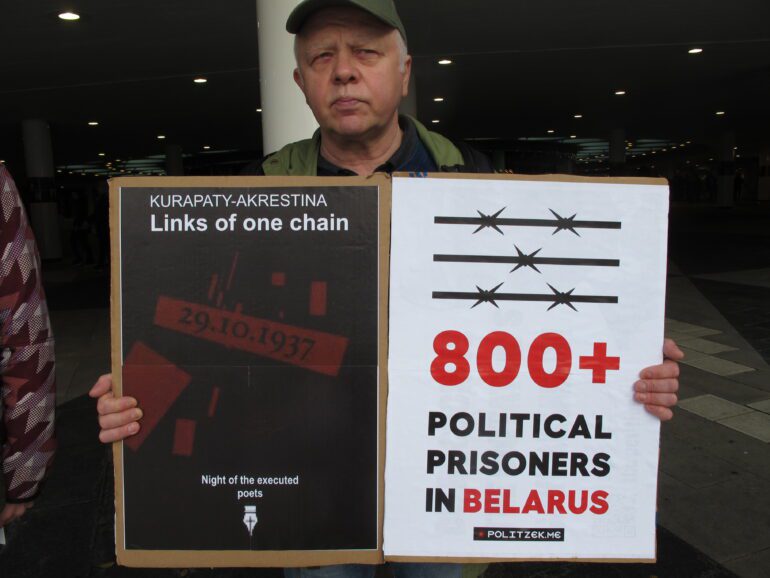

Through these different measures, the Danish government is effectively hollowing out the principle of asylum. The paradigm shift has placed refugees in a condition of protracted risk of deportation. The model was tried on refugees from Somalia in 2016; in 2020, migration authorities’ attention turned to Syrian refugees. In 2019, Denmark became the first country in Europe to withdraw protection status for Syrians who had fled the ongoing war. Syrian refugees in Denmark received letters stating that their protection status had been revoked and were called in for so-called repatriation conversations with authorities. Many appealed their decisions to the court-like Refugees Appeal’s Board. Some won their case, and were granted stronger protection status; others had their deportation orders affirmed. The Danish government does not have a readmission agreement with the Assad government in Syria, and those refugees who refuse to leave Denmark are therefore sent to deportation camps. The Danish government has increased the cash support for so-called assisted voluntary return, but very few have chosen to accept the money, which critics argue would practically mean selling their right to asylum. Some have gone underground or left Denmark to other European countries to seek asylum there. Others have resisted by organizing demonstrations and sit-in strikes to protest the inhumane asylum system and the paradigm shift. They have gained support by the Danish public: in November 2021, over 50 000 people signed a citizen’s initiative to stop deportations to Syria. So far, however, the Danish immigration authorities have not changed their praxis.

In October 2021, I spoke to two of the prominent activists who have partaken in the demonstrations against deportations of Syrians and against the inhumane treatment of refugees in Denmark under the paradigm shift. We talked about how the paradigm shift has affected people who sought protection in Denmark, and about the importance of continuing the struggle and challenge the country’s dangerous deportation-oriented asylum policy.

A conversation with Emad Alhabi, Syriske forening Danmark, and Fedaa Sultan, Activist and Cultural Worker.

How would you describe the conditions facing Syrian refugees in Denmark right now?

The Syrian population in Denmark is split into two groups: on the one hand, those who are not affected and struggling to become part of society and live up to the government’s integration requirements, which entails among many other things working fulltime for three and a half years to gain permanent residency. And on the other hand, there are those who have subsidiary, temporary protection statuses. They are currently living in constant fear of having their cases reopened and re-evaluated, and risk being sent back to Syria if they are from the Damascus or its Rif areas. A terrifying condition to be in. An estimate of 4 200 people are to be subjected to re-evaluation; and in my opinion they are using this limited group as an experiment.

How has the paradigm shift impacted refugees in Denmark?

Of course, these laws are targeting all refugees. Those working for permanent residence permits had also been targeted; all refugees are affected. The repressive paradigm shift was initiated by the previous minister of immigration and integration, Inger Støjberg during her time in office. It’s a package of laws targeting all refugees with the sole aim to make their lives miserable. For instance, studying used to be considered equivalent to work but this is no longer the case. So now people are forced to quit their studies and take up fulltime work, which is an obstacle to integration, in our opinion. Another example is that you must renew your permit – and with it, your Danish travel document – every two years. Because you need both documents to travel your freedom of movement is highly restricted during the time of re-evaluation. Many Syrians have friends and family scattered across Europe and they are deprived of the possibility to visit them during this time. They have of course also made it harder to obtain permanent residence status or citizenship: before it was 6 years, now 8 years before you can obtain permanent residency. This is just to highlight that the paradigm shift is more comprehensive and has not only affect those from the Damascus region, who have their residence permit withdrawn.

What happens to those who lose their residence permit?

Of course, it comes as a big shock when they receive the letter from the immigration service. Those who have temporary status and are aware of this risk live in constant fear; others might forget about it, and when they receive it, they get a shock. There are multiple examples of people getting heart attacks or become paralyzed from receiving the news that they are now facing deportation. People are brought back into the same mindset they were experiencing in Syria under the dictatorship.

Many Syrians became watchful when they first came to Denmark, when they realised the suspicious attitudes towards refugees there, and were placed in the camps. The camps brought us back to Syria and reminded us of how people would be incarcerated under the regime. Syrian refugees now started watching their words, afraid of saying something that might be misinterpreted and used against them by the immigration service. Attending the meetings with the immigration service was almost like an interrogation: the techniques they used, the way the caseworkers were fishing for any contradiction in your story and use it against you… it’s very traumatizing. At the end of the meeting, they would compel you to sign a document as a proof that you have accepted the story as it was told. This process was very stressful to go through, knowing that any inconsistency or mistake would be used against us.

This treatment made many of us adopt the same state of mind and behaviour they had under the dictatorship. It’s a terrifying mental state to be in. Syrian refugees do not trust the intentions of the Danish government, or whether they will protect their human rights. When the Danish government claims that Damascus is safe, they don’t consider what the situation is like on the ground: that people have lost everything, that they have had their homes demolished and flattened with the ground. All they look at when they reassess our cases is whether you are persecuted. But for some, it’s not only about personal persecution, but about a family member who has been engaged in anti-government activities, which also puts you at risk of being arrested and tortured, as the regime will try to get information about that person whom you might barely know yourself. In almost every family, there is someone who has been engaged against the regime one way or the other, and who will be considered a suspect.

Do people actually go back to Syria if they receive a deportation order from Danish authorities?

When people receive a negative decision, they react very differently. Some have the will and power to resist. They appeal and fight to reopen their case. But not all people have the resources to, and some believe when they receive the letter of rejection that it is final, and don’t even think that they can appeal. This distrust for the Danish system pushed some to leave Denmark at an early stage and move on to another EU country. Some of them were forced back to Denmark (under the Dublin Regulation), but others are now in refugee camps in other European countries after having stayed underground for a year and then applied for asylum. This distrust in authorities leaves a deep mental scar among Syrians – and among refugees in general. Even those of us who have refugee status are considering whether we want to stay in Denmark or not. It makes us unmotivated and afraid to invest too much in our future in Denmark when we know we might be forced to leave at any time.

The laws are primarily affecting elderly people, and women. The majority of those under threat of deportation are women. People who arrived as children who then turned 18 will also have their residency re-evaluated and they are treated as a separate case even though they have family members living in Denmark who are not affected. This is terrifying. Some women are just worn out that they marry someone they barely know as a last resort to avoid deportation. This group is the one facing the worst threat. Some might go underground, but not everyone have the strength, the capacity and resources to do so.

In what ways are people challenging their deportation orders?

We try to resist. We held the sit-in protest in front of the parliament, which lasted for a month and a half between May-June 2021. It was an attempt to draw public and media attention to how bad the situation is. This was our only way out. When people lose their residency, they lose everything: the right to work and study, the right to benefits. Older people, and people disabled from injuries they acquired in the war, lose their only way of sustaining themselves. They are forced to into deportation camps if they don’t have the ability to go underground or move to another country. But resisting requires a lot of mental and physical strength, especially if you try to leave together with your family; and it is not a solution for everybody. So, some are forced to go to deportation camps, and the conditions there are terrifying – the hygiene, the conditions and standards, the way people are treated… and the atmosphere there is depressing. There are now 180 Syrians living in Kærshovedgård deportation camp.

What are the next steps in your struggle?

We have reached a stage where we need to raise this issue internationally. We want to bring cases of Syrian refugees in front of the European Court of Human Rights, and raise awareness on the international level or how inhumanely refugees are treated in Denmark. We will learn from the knowledge we developed during the protest, and use this knowledge to encourage people to take action. When people receive a rejection, many get isolated from society, and some don’t even get to fight to get their residency back, since it requires a lot of energy to take on that fight. Not everyone has the knowledge and is ready to do that. Therefore, we plan to make a nation-wide campaign where we encourage local initiatives to support Syrian refugees, to break their isolation, and to unite the struggles of Syrians with other refugee struggles and local initiatives in Denmark. Because this is not only about Syrians, but about all refugees subjected to the paradigm shift, and to the horrible conditions in the Danish deportation camps. This is why we need to join forces and continue the struggles together.